Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) play a critical role in research labs - they help ensure reproducibility, support regulatory compliance, and keep day-to-day operations running smoothly.

That said, if you’ve ever felt overwhelmed trying to write, manage, or enforce SOPs in your lab, you're in good company. Between regulatory requirements, staff turnover, and the ever-evolving nature of lab work, maintaining relevant, current, and consistently followed procedures is not an easy task - especially when you're juggling research deadlines and cross-functional workflows.

As scientists who’ve spent years at the bench, and who’ve seen our fair share of SOPs (some good, some bad, and everything in between), we know how tricky SOP Management can be. These days, we spend our time helping fellow scientists untangle and solve those documentation challenges (and loving it!).

So, we decided to put together a practical, user-friendly resource for life science researchers looking to start using SOPs or improve how they manage them.

Now before we dive in, a quick but important disclaimer: This blog is in no way a formal compliance resource and shouldn’t replace official regulatory or legal guidance. We can’t offer compliance advice, as requirements can vary widely by region, jurisdiction, and the specifics of your lab's operations. Plus, regulations do evolve over time. We strongly recommend speaking with a qualified regulatory or legal expert to assess the regulatory requirements for your particular use case.

With that out of the way, let's dive in, shall we?

Understanding Standard Operating Procedures

What are SOPs?

Standard Operating Procedures are detailed, written instructions that lay out exactly how to perform a specific process, assay, or task - step by step - ensuring consistent execution and reliable results every time.

While SOPs are seen by many as just a regulatory necessity, in reality they’re the unsung heroes of quality in life science and biotech labs.

They make sure every assay and task is performed the exact same way - by anyone, from the most junior technician to your lead scientist, on any day. That level of consistency is what makes your data reliable today and reproducible months or even years down the road.

And as your lab grows, brings in new team members, or adopts digital tools like an Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) or LIMS (Laboratory Information Management Systems), having a solid SOP foundation only becomes more valuable.

Why are SOPs important in the lab?

Well-written SOPs help to:

- Streamline training and onboarding: New team members can follow clear, step-by-step instructions from day one. This not only reduces reliance on informal knowledge transfer, and frees senior staff from repetitive demonstrations, it also creates a consistent training standard across departments and labs, ensuring every team member learns and performs assays and procedures in exactly the same way.

- Support reproducible science: Standardized protocols eliminate guesswork. Whether you’re troubleshooting an assay or scaling up production, SOPs let you compare data confidently across experiments, teams, or even different research sites.

- Simplify regulatory compliance: When you have well-written SOPs aligned with Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), or other industry standards, compliance becomes part of the everyday workflow. They help ensure your team knows what’s required and consistently applies the rules in their daily work.

- Stay audit-ready: An organized SOP repository makes it easy to retrieve the current protocol - and its version history - in seconds, so you can respond to auditor requests without delay.

SOPs and Their Role in Regulatory Compliance

As we’ve hinted at a few times now, SOPs aren’t just a good practice, they are a regulatory must-have and need to withstand scrutiny from regulatory bodies for research teams in regulated industries. Under GLP and GMP, for example, every critical operation - from sample handling to equipment maintenance and data recording - requires its own approved procedure. The FDA, EPA, OECD, EMA, and ISO guidelines also frequently mention SOP requirements, with regulators often requesting to review SOPs during audits or inspections.

In fact, “Deficient Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)" are among the most frequently cited deficiencies in Form 483 and Warning Letters from the FDA. The FDA frequently flags SOP issues such as:

- Missing SOPs for essential processes - such as instrument calibration or sample storage

- Written procedures not followed in practice - When day‑to‑day workflows drift from the documented steps, you risk inconsistencies and inspectional remarks.

- Obsolete versions still in circulation - Without strict version control, outdated protocols can linger in use long after they’ve been superseded.

- No training records - Auditors expect signed, dated evidence that every team member has been trained on the current SOP.

- Incomplete change‑control history - Missing version numbers, approval signatures, or revision logs make it impossible to trace how a procedure evolved.

During an inspection, it’s not uncommon for auditors to ask for a list of all SOPs, select a few at random, and then verify both the documents and corresponding training records. Demonstrating rigorous change control - where each SOP is current, properly approved, and fully documented - will go a long way toward a smooth audit.

Now you might think - like I did when I first tackled SOPs - that since the FDA places such heavy emphasis on them and flags deficiencies so regularly, they’d offer a standardized template or at least clear, detailed guidelines on how to structure an SOP and what content it must include.

I remember spending countless hours combing through FDA guidance documents, trying to pin down exactly how an SOP “should” look and what it needed to include.

Here’s the surprising truth: there isn’t one official FDA definition or format for SOPs. Instead, they’re mentioned across several regulations:

- 21 CFR Part 211 (cGMP for drug manufacturers)

- 21 CFR Part 58 (GLP for nonclinical laboratory studies)

- 21 CFR Part 820 (QSR for medical devices)

- 21 CFR Part 11 (electronic records and signatures)

Reading those regulations makes one thing clear: the FDA doesn’t mandate a single SOP template or specific layout - SOPs are merely described as written procedures that accurately describe and detail essential job tasks. That means your organization needs to decide how you’ll format your SOPs and what information each one will include, based on your workflows, your product, and the rules that apply to you.

In Europe, GMP requirements are laid out in EudraLex Volume 4, which provides helpful details on which activities should be governed by SOPs - such as the receipt, sampling, and testing of materials - and highlights key information these procedures should include. For non-clinical laboratory studies, the relevant regulation is Directive 2004/10/EC - which in turn aligns with the OECD’s GLP principles . These documents mandate SOPs for a wide range of lab activities, to ensure that critical processes are clearly documented and carried out consistently.

While these guidelines clearly indicate where SOPs are needed, they don’t prescribe a single, official definition, and they don't mandate a specific structure or scope for SOP documents.

There's just a consistent expectation across all guidelines that procedures are documented, approved, controlled, and reviewed regularly - leaving it up to each organization to determine the format and level of detail that best supports their workflows and compliance needs.

Now you might be thinking, “Great - thanks for nothing!”, and I don’t blame you.

I remember years ago, while working at a small biotech startup, I was staring at a blank Word document - tasked with writing our company’s first official SOP and unsure what to include or where even to begin. Sure, I had protocol write‑ups for various assays, but were they detailed enough? What else needed to be covered? And if the FDA ever came knocking, what would they expect to see?

Fortunately, you’re not the first scientist to tackle SOP creation - thousands of labs have already navigated these regulations and developed established SOP structures that you can adapt to your lab’s needs. We'll outline one possible SOP structure below to give you some ideas.

If you look closely at the various guidelines listed above, they converge on a clear SOP blueprint: every procedure should have a defined scope, designated roles and responsibilities, detailed step‑by‑step instructions, a documented change‑control history, and proof of training.

Before we dive into an example SOP outline...

Here’s what is generally expected from SOPs

1. They should be written and controlled documents

- Typed, version-controlled, and dated.

- Signed off by responsible personnel.

- Properly archived so that previous versions can be retrieved when needed.

2. They should be specific and detailed

- Include enough detail so the task can be reliably repeated by different individuals.

- Clearly outline safety precautions, equipment settings, procedural steps, handling instructions, and any documentation requirements.

3. They must cover key operational areas

Depending on your type of lab or facility, SOPs are expected for areas like:

- Equipment use, cleaning, and maintenance

- Sample collection, receipt, handling, and storage

- Data recording and handling (especially under GLP or 21 CFR Part 11)

- Managing deviations and out-of-specification results

- Training procedures and qualification records

- Material and inventory management (e.g., reagents, compounds, reference standards)

- Documentation practices (e.g., ALCOA principles)

- Change control and version updates

- Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA)

- Internal audits and QA oversight

Guide to Writing Good Standard Operating Procedures

Planning out your SOP framework

Before you start writing, look at the bigger picture: The first step in building a solid SOP system is to map out the processes and workflows your team uses regularly. This doesn’t need to be complicated, (or pretty) but it does mean stepping back and taking stock of how work actually gets done. Start by listing out the core activities across your team or organization: things like equipment calibration, sample tracking, or data entry and review.

Talk to the people who carry out these tasks. Chances are, they’ll surface steps or variations that aren’t written down anywhere yet, or there may be some protocol documents already in existence somewhere that you can use as a reference point when drafting your SOPs.

Once you have a complete view of the workflows, group them into logical workflow units and tackle one unit at a time. This makes SOP creation more manageable and helps ensure you don’t overlook any critical steps. Just as important, it helps you understand how your SOPs relate to one another. That way, when you revise one SOP - say, for data analysis - you can quickly see which upstream or downstream SOPs might also need to be reviewed or updated. A clear map of interconnected workflows gives you the structure to maintain consistency, reduce redundancy, and adapt your procedures over time without losing track of what’s linked to what.

Recommended SOP Structure: A strong framework to set you up for success

Once you've mapped out your processes and identified the SOPs you need, start with one workflow and approach it methodically. For an SOP to truly add value, it has to be more than just a document sitting on a shared drive or collecting dust in a binder. It should be a practical, day-to-day resource your team can actually use.

Remember, detail is key! To quote the official EPA Guidance for Preparing Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) “SOPs should be written with sufficient detail so that someone with limited experience with or knowledge of the procedure, but with a basic understanding, can successfully reproduce the procedure when unsupervised”.

Begin by aligning on a consistent format that all teams in your organization can use. Check in with other departments early to make sure the structure fits everyone's needs.

As you write, keep instructions simple and clear and write from the perspective of the end-user. Use short sentences, familiar terms, and avoid unnecessary jargon. Define any abbreviations or technical terms the first time they appear. Mark optional steps clearly and explain how they impact the workflow. Use precise language. Avoid vague terms like “periodic” or “typical”, which leave room for interpretation. Choose strong, direct verbs for required actions like “must,” “add,” or “incubate”. Make sure the SOP is written by someone with hands-on experience - ideally, a subject-matter expert who’s actually done the work.

And lastly, SOPs must be distributed and acknowledged promptly with training logs to demonstrate compliance.

With that in mind, here’s our step-by-step guide to structuring SOPs - section by section. We’ve included examples to help you get started, if you’re currently creating or reviewing SOPs.

1. Title Page

Start every SOP with a clear cover page. People reading the SOP should know exactly what they’re looking at, who it applies to, and whether it’s the most current version.

The title page should include a descriptive title, a unique SOP ID and version number, and the date it was issued or last revised. Be sure to note which research site, department, or team the SOP applies to, and include the names and dated signatures of those who authored, reviewed, and approved it.

Be sure to include the date of the most recent review - it helps ensure the SOP remains current and relevant.

2. Table of Contents

If your SOP covers a complex process or is very long, it is advisable to add a table of contents for easy reference.

3. Purpose/Objective

The purpose should briefly (in 1 or 2 sentences) define the intent of the document and what objective the SOP is intending to achieve.

Example: This SOP describes the standardized procedure for performing Western Blotting to detect and quantify specific proteins from complex biological samples using SDS-PAGE, membrane transfer, and antibody-based detection.

4. Scope & Applicability

The scope section describes the exact process, task, or experiment the SOP applies to and defines the start and end points of the procedure. When writing this section try to be specific and avoid room for interpretation. Also make sure to list any limitations or exceptions not covered by the SOP.

Example: This SOP outlines the procedure for detecting a protein of interest in cell homogenate samples using Western blotting, beginning with sample preparation and continuing through electrophoresis, membrane transfer, antibody incubation, and detection via chemiluminescent imaging. It includes all required materials, reagent preparation steps, and safety considerations, including the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) for handling chemicals involved in the process.

This SOP does not cover maintenance, calibration, or troubleshooting of the equipment used (e.g., electrophoresis systems, imaging hardware). For those procedures, please refer to SOP-002: Equipment Maintenance and Calibration.

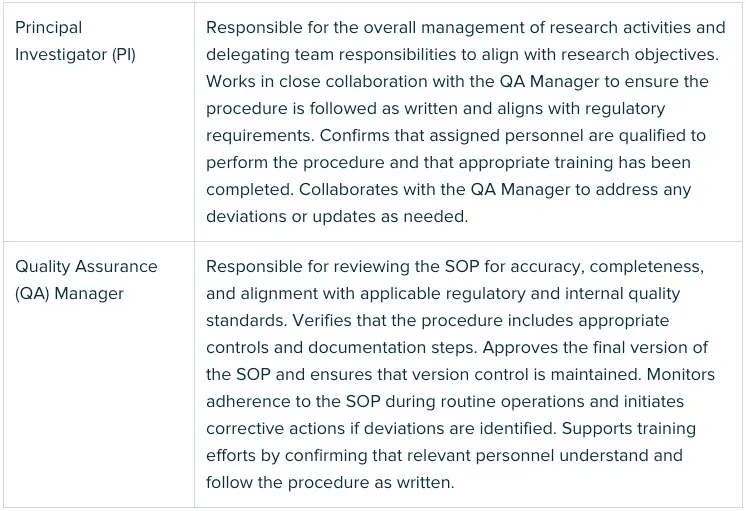

5. Qualifications, Roles and Responsibilities

Clearly state what level of experience or training the user should have to perform the procedure properly, and mention any requirements like certifications. Specify who is responsible for carrying out the procedure, reviewing the SOP, and approving it. Include roles such as Scientists, QA staff, and management to ensure accountability.

Tip - Lay it out in a simple table - one column for Role, another for Responsibilities - so everyone’s duties are visible at a glance.

Example:

6. Definitions and Abbreviations

List and define any technical terms or acronyms used in the SOP that might not be familiar to all readers. Remember, your SOP should be just as clear to a new graduate fresh out of college as it is to a seasoned scientist. Keep it alphabetical for quick reference.

Example:

- BSA: Bovine serum albumin

- PBS: Phosphate Buffered Saline

7. Materials and Equipment

List all materials (reagents & consumables) and equipment (including hardware & software) required to carry out the procedure, including specifications and acceptable alternatives if applicable.

If applicable, include detailed instructions for instrument calibration or method standardization, or reference any related SOPs or documents that cover this information.

Tip - break this section down into different sub-sections for:

- a. Reagents

- b. Consumables

- c. Equipment

For equipment, be sure to list any specific settings required for the procedure - such as a water bath set to 38 ± 0.2 °C - and instruct users to verify the settings before starting. They should also document that the equipment was checked and correctly configured. This is especially important in shared lab spaces, where equipment may be adjusted frequently for different protocols.

If your procedure involves working with samples, especially those received from outside your lab, it’s a good idea to include a dedicated subsection describing how those samples should be collected, preserved, stored, and handled. Clear documentation here helps protect sample integrity and supports both reproducibility and compliance. If your lab operates under specific regulatory frameworks - such as HTA (Human Tissue Authority) in the UK or HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) in the US - be sure to include details on how samples and any associated data must be logged, tracked, and stored in accordance with those requirements.

8. Safety

A well-written SOP should include a dedicated safety section outlining all required Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), along with any chemical or biological hazards associated with the procedure. Be sure to note any prerequisite safety training required to handle these materials, and highlight any special handling or storage considerations for the reagents and equipment involved. If there are specific safety forms - such as COSHH forms in the UK - include their ID numbers and titles so team members can quickly locate and review the relevant information.

If the procedure must be carried out in a specific location, such as a designated room or area within the lab, be sure to clearly state where it is permitted (e.g., under a fume hood in the chemistry lab). Specifying the correct location helps ensure the work is done safely and with the proper containment or environmental controls in place.

Example: All necessary PPE outlined in this document must be worn at all times while carrying out this procedure. This SOP involves the use of hazardous substances including phenol and chloroform. The procedure must be conducted in the designated chemical fume hood located in the chemistry lab, to ensure proper ventilation and containment. Only trained and authorized staff may carry out this work. Before starting, review the relevant COSHH assessments:

- COSHH-007: Phenol – Health Hazards and Emergency Measures

- COSHH-009: Chloroform – Safe Handling and Disposal

COSHH forms are available in the safety binder and on the shared lab drive.

9. Step-by-Step Procedure

The heart of your SOP. Here you should detail each step in sequential order, using clear, concise language.

Tips:

- Break steps into numbered or bulleted lists for quick scanning.

- Remember to use clear, concise language. Avoid unnecessary detail.

- Where appropriate, add flowcharts or diagrams; visuals often communicate processes more clearly than blocks of text.

10. Quality Controls (QC) and Quality Assurance (QA)

Your SOP should clearly outline how to assess the success of the procedure. Outline how to record results, and log any deviations. Provide instructions on data recording to ensure traceability.

Be sure to include details on

- Suitable Controls: Include positive (known active) and negative (blank/deactivated) controls, plus loading controls where appropriate (e.g., GAPDH or β‑Actin for western blots)

- Calibration & Frequency: Define how often instruments should be calibrated (e.g., monthly/quarterly) and describe any routine QC self-checks or verification procedures that should be performed to ensure equipment and methods are performing as expected.

- Acceptance Criteria: Set clear limits (e.g., signal‑to‑noise ≥3:1, ≤1.5‑fold loading‑control variation) and state the expected outcomes for positive/negative controls.

- Corrective Actions: If criteria fail, define the exact steps to take, e.g., re-check sample quality, repeat the run, or service /recalibrate instruments etc.

- Documentation: Clearly state what QC data must be saved (e.g., calibration certificates, band images, corrective action records), where it should be stored (e.g., in a LIMS or QC logbook), and ensure all entries are signed and dated to maintain full traceability.

11. Data and Records Management, Data Analysis and Calculations

Your SOP should include a section on Data and Records Management, outlining how and where data generated during the procedure should be recorded, analyzed, and stored. Specify any required calculations, forms to be completed, or reports to be submitted as part of the process. If a particular software tool or analysis method is needed, include a brief but clear description of how it should be used. For more complex or multi-step analyses, it’s best to reference a separate SOP that details the full analysis workflow, ensuring this document stays focused while still pointing users to the necessary resources.

12. Decontamination/Waste disposal

If your work involves hazardous materials - such as contagious biological agents (e.g., Adeno- or Lentiviruses), Genetically modified organisms (GMO)s (e.g., under bioCOSHH (biological Control of Substances Hazardous to Health) in the UK), chemical hazards, human-derived samples, radioactive material, or carcinogens - proper waste disposal procedures must be clearly outlined here.

Reference any materials flagged in Section 8 - Safety, and specify the necessary disposal steps for your laboratory: autoclaving, decontamination, or incineration.

Example: All contaminated waste must be autoclaved before disposal. Please ensure the appropriate bin logs are updated and noted in your write-up.

13. References and related documents

List any documents (equipment manuals, templates) or related SOPs that are needed to understand and properly execute the procedure.

For example, an SOP describing the use, calibration, maintenance and sample acquisition on a specific flow cytometer should be referenced in an SOP describing the staining of cells for analysis by said flow cytometer.

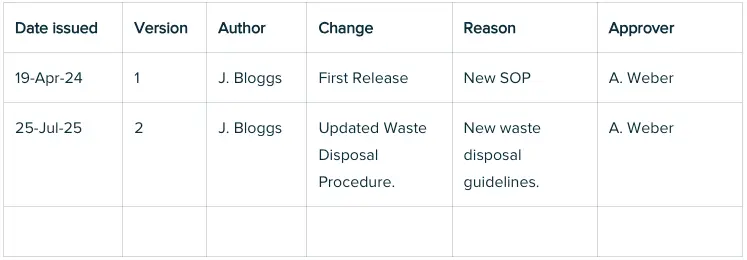

14. Revision History

A clear revision history within an SOP is crucial for regulatory compliance and quality, as it enables teams to easily track what changed, why, when, and by whom. Including this history directly in the SOP - preferably in a table format - supports transparency, accountability, audit readiness, and effective version control without needing to reference other documents.

Example table:

15. Training Record

Some labs choose to attach the training record directly to each SOP, while others maintain separate records - either one per SOP or a centralized record for each employee that tracks which SOPs (and versions) they’ve been trained on. How you organize your training records is up to you and should reflect your team’s workflow and preferences.

What matters most is that you maintain a complete, verifiable record showing who has been trained on which version of each SOP. This record should include the user’s signature and the date they confirmed they’ve read, understood, and agreed to the responsibilities outlined - before they carry out the procedure for the first time.

Mastering SOP Management

Now that your SOP is written, the real work begins....

Managing SOPs is more than just writing documents and saving them somewhere. The real challenge lies in keeping SOPs up to date, accessible, and integrated into daily lab routines.

In this section, we’ll cover tips on how to maintain your SOPs over time - from version control and review schedules to training and accessibility - and how to avoid common problems many labs face in their SOP management.

Common Challenges Labs Face When Managing SOPs

Even the best-written procedure doesn’t help your team or your compliance efforts if no one follows it (or even knows where to find it) and many labs face the same frustrating challenges:

1. Version Control Confusion

- final_FINAL_reallyfinal_v3 – Sound familiar? When SOPs circulate via email or are saved in multiple folders, version control becomes chaotic. Different team members may have slightly different versions, leading to inconsistent practice and compliance risks.

2. Document Accessibility Issues

- Nested folder systems, multiple shared drives, or physical ring binders can turn finding the right SOP into a frantic scavenger hunt, especially under audit pressure (we’ve seen it happen).

3. SOPs Not Reflecting Reality

- Procedures evolve, but SOPs often lag behind. Researchers might routinely skip or modify steps without updating the document, undermining reproducibility.

4. Lack of Formal Review and Approval

- Without a clear review and sign-off process, it’s difficult to hold anyone accountable for the SOP’s accuracy or adherence to regulatory requirements.

5. No plan for when things don’t go according to plan.

- Lab work is often unpredictable - machines malfunction, samples arrive late, or environmental conditions aren’t quite right. Maybe the centrifuge didn’t cool to the required temperature, or the tissue culture hood was unavailable because the previous user ran over by an hour, delaying your treatment or readout. These kinds of deviations are common in real-world lab settings. But when they happen and go unrecorded, undocumented workarounds can introduce inconsistencies, making it difficult to trace what really happened. This not only affects data quality and reproducibility but can also create compliance risks.

6. What Language is this?

- It sounds obvious, but SOPs should be written in the primary language your team actually uses, and the terminology should be clear and straightforward. If people have to translate the SOP or decode layers of technical jargon, there’s a good chance it won’t get followed.

7. Incomplete Training Records

- SOPs that aren’t integrated into your lab’s daily workflow often get missed during training and overlooked during onboarding. Failing to document who was trained on which SOP version can cause serious issues during inspections and audits.

8. Version? What Version?

- Researchers often forget (or skip) recording which SOP - particularly which version - they followed, making reproducibility a guessing game.

These common challenges are just that. Common. Many labs struggle to manage their SOPs effectively. It’s the can of worms that no one wants to open, mainly because it’s usually a bigger task than first imagined and no one has the time. But ignoring it doesn’t make it go away. The key is to tackle these challenges as a team: update what’s missing, clean out what’s outdated, and clarify what’s still in use. And if it’s been a while since you thought about the full SOP lifecycle, don’t worry - we’ve got a quick refresher coming up next.

The SOP Lifecycle: Managing SOPs as Living Documents

If you’re new to SOPs, you might not be familiar with the term “SOP life cycle.” But the full process an SOP goes through: from drafting and review, to approval, implementation, regular use, periodic review, and eventually updates or retirement (archiving) is all about making sure your SOPs evolve alongside your team, staying accurate, remain relevant, and are actually useful in practice.

1. Drafting stage

This stage should always involve input from the people who perform the process. The end users, technicians, and staff who execute the procedure will have insights that capture practical nuances and safety considerations often missed by those who don’t perform the work regularly.

2. Internal Review and Peer Feedback

Share the draft with peers and subject matter experts to catch errors, improve clarity, and ensure consistency with related SOPs or policies.

3. Testing by a Fresh Pair of Eyes

Assign someone unfamiliar with the procedure to follow the SOP step-by-step. This test reveals ambiguous instructions or gaps. Simultaneously, experienced staff should verify that outcomes match expectations.

4. Formal Approval

Route the final SOP through your QA lead, department head, or other designated approvers for official SOP sign-off. This step ensures that the SOP meets regulatory and quality standards.

5. Training and Documentation

Train all relevant team members on the new or updated SOP. Document who was trained, when, and on which version. From a regulatory standpoint, it’s critical to record not just who was trained, but also which version of the SOP they were trained on. Auditors often look for this level of traceability to ensure compliance, especially in regulated environments like GLP, GMP, or ISO-certified labs.

6. Controlled Distribution

Store and distribute only the approved, current version of the SOP through a centralized system. This prevents outdated copies from being used inadvertently.

7. Auditing and Periodic Review

Review the SOP’s effectiveness after it’s been in use - ideally ~1 to 3 months after implementation. Then schedule periodic reviews (annually or biannually) to ensure the content is still accurate, relevant, and aligned with current practices and regulations.

8. Change Management and Revision Triggers

However, don't just rely on a scheduled document review, but have a system in place to flag when an SOP needs to be revisited. Triggers might include process changes, new equipment, audit findings, deviation reports, or team feedback. These are early warning signs that the SOP might need an update, even if it’s not “due” for review.

9. Archiving and Version Control

Retire obsolete SOP versions systematically, archiving them with detailed revision histories including who made changes, when, and why. This traceability supports investigations, audits, and regulatory submissions.

In summary, SOPs are not static. They evolve with new workflows, equipment upgrades, regulatory changes, and lessons learned from audits or deviations. Managing this lifecycle effectively ensures your SOPs remain relevant and reliable.

But remember, managing SOPs effectively goes far beyond simply storing documents - it means tracking the full context behind every version. You need clear records of who created, reviewed, and approved each SOP, what changed and why, who was trained on which version, and when each version was created, updated, or retired. This level of detail supports both internal oversight and external audits, ensuring your team can always show exactly what happened, when, and why.

While it’s possible to manage all this manually with ring binders and spreadsheets, it quickly becomes time consuming, error‑prone, and difficult to scale. Even small gaps, like forgetting to log which version was followed, can snowball into compliance risks or force costly experiment do‑overs.

That’s why, as your organization grows, we’d recommend investing in digital tools to manage your SOPs and laboratory documentation.

Using digital systems for managing SOPs

Digital SOP management tools vary widely, so the right choice depends on your team’s needs. Traditional Quality Management Systems (QMS) (like MasterControl or Veeva Vault) handle version control, approvals, and audit trails well but often sit apart from day‑to‑day lab workflows, leaving scientists to manually link SOPs with experimental data and inventory records.

Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs) and Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) are great for capturing experiment details and tracking samples - but most stop there, offering little or no support for SOP management.

That’s where integrated solutions like IGOR stand out. IGOR combines SOP creation, approvals, versioning, deviation tracking, and archiving directly with experiment and sample management, keeping your SOPs connected to day-to-day lab activities.

What’s more, IGOR’s ELN brings together your notes, write-ups, SOPs, inventory, and files in one intuitive interface - complete with audit trails and digital signature workflows for full traceability. This makes it easy to follow the complete story of your experiments - from the materials you used, to the SOPs you followed, to the results you achieved.

But enough about IGOR... (sorry, we can't help it, we just love the tool we've built!)

Overall, the right tools should make SOPs easier to manage, easier to follow, and easier to trust. If you’re on the market for a digital system, here’s our list of essentials to look for:

- Approval Tracking, Version Control & Digital Signatures: Know exactly who created, reviewed, and approved each SOP with time‑stamped audit trails and secure, 21 CFR Part 11‑compliant digital signatures. Versions should be easy to view and compare -showing what changed, when, and why - while remote approvals keep the process smooth, compliant, and paper‑free.

- A centralized SOP library: Everyone on your team works from the same, up-to-date version. No more hunting through folders or risking the use of outdated procedures. Previous versions can be easily archived with full access when needed for reference, audits, or investigations.

- Standardized templates ensure that every SOP follows the same clear, logical format. This not only makes them easier to read, train on, and audit, a consistent structure also reduces the chance of important details being left out.

- Linked Execution & Deviation Logging: The most effective systems connect your SOPs directly to experiment records and sample usage logs. You should be able to record deviations and results as they happen, without modifying the original SOP, ensuring traceability while protecting document integrity.

- Easy Access & Integration: When SOPs are part of the same platform your team uses to manage experiments and inventory, they’re easier to find, follow, and trust. That integration makes it more likely that SOPs are used correctly and consistently. And it saves A LOT of time.

In short, having the right digital tools should streamline compliance and ensure SOPs are part of your lab’s everyday workflow. If you’re on the market for a new system, go armed with a list of essentials your new system must have and be sure to explore the market fully - the biggest names might not always be the best match to your needs.

We hope you find this blog post helpful! If you do, please leave us a comment or like the post, so we know it is useful! And if you spot anything that’s missing or could be improved, we’d love to hear from you! Just drop us a note at info@igorlabapp.com. We’re always updating our resources to make sure they stay useful and relevant.

Glossary of Abbreviations used in this blog

Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 11 (21 CFR Part 11)

A regulation issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that defines the criteria under which electronic records and electronic signatures are considered trustworthy, reliable, and equivalent to paper records and handwritten signatures. 21 CFR Part 11 applies to organizations that use electronic systems to create, modify, maintain, archive, retrieve, or transmit data required by FDA regulations. Compliance involves controls such as secure user access, audit trails, validation, record retention, and signature authentication to ensure data integrity and traceability.

EMA – European Medicines Agency

The EMA is the regulatory body responsible for the evaluation and supervision of medicinal products in the European Union. It ensures that medicines are safe, effective, and of high quality before and after they reach the market. The EMA plays a role similar to the FDA in the U.S.

EPA – Environmental Protection Agency

The EPA is a U.S. federal agency that regulates chemicals, pesticides, and environmental pollutants to protect human health and the environment. In life sciences, the EPA often oversees studies related to toxicology, environmental exposure, and pesticide safety.

FDA – U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The FDA is the U.S. federal agency responsible for protecting public health by regulating the safety, efficacy, and quality of food, drugs, biologics, medical devices, and more. In the life sciences, the FDA reviews clinical trial data, approves new drugs and therapies, inspects facilities, and enforces compliance with regulations like GLP and GMP.

GLP – Good Laboratory Practice

GLP is a quality system used in non-clinical safety testing (e.g., animal studies, chemical testing). It ensures the reliability, consistency, and integrity of laboratory data submitted to regulatory authorities like the EMA, EPA, or FDA. It applies to how studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, and reported.

GMP – Good Manufacturing Practice

GMP covers the manufacturing and quality control of pharmaceuticals, biologics, and medical devices. It ensures products are consistently produced and controlled according to quality standards. GMP is essential for both clinical and commercial product manufacturing and includes everything from raw materials to personnel hygiene.

HIPAA – Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (US)

HIPAA is a U.S. federal law that sets standards for the protection of individually identifiable health information (often referred to as Protected Health Information, or PHI). In research settings, HIPAA governs how personal health data is collected, stored, accessed, and shared - ensuring patient privacy and data security, particularly in clinical studies and health-related data analysis.

HTA – Human Tissue Authority (UK)

The Human Tissue Authority (HTA) is the regulatory body in the United Kingdom responsible for overseeing the removal, storage, use, and disposal of human tissue for research, medical treatment, education, and training. The HTA ensures that all activities involving human biological materials comply with the Human Tissue Act 2004, emphasizing informed consent, ethical use, and proper record-keeping.

ISO – International Organization for Standardization

ISO is an independent, non-governmental international body that develops voluntary global standards across industries. In life sciences and biotech, ISO standards (such as ISO 9001 for quality management or ISO 13485 for medical devices) help organizations ensure quality, safety, and efficiency in their processes, products, and services. ISO compliance is often key for international collaboration and certification.

OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

The OECD is an international organization that develops policies to promote economic growth and well-being. In scientific and regulatory contexts, the OECD is known for its GLP principles and test guidelines, which are widely adopted by member countries to ensure consistency and mutual acceptance of data in non-clinical safety testing (e.g., toxicology studies).